15 Of My Favorite Gadgets From Movies & TV That Are Totally Absurd

Since the beginning of the moving picture, television and movies have given us an impressive selection of fictional gizmos and gadgets. Common real-world technologies, ranging from submarines to spacefaring rockets and from video phone calls to tablet computers, all have their origins in the pages or frames of fiction.

Authors and filmmakers regularly invent new technologies to solve story problems, and sometimes those fictional gadgets become so popular that real-world engineers and inventors set about making them real. "Star Trek's" communicators, for instance, were effectively realized with the invention of the mobile phone. The original communicator even looked like the now-antiquated flip phones popular at the beginning of the millennium.

Other fictional inventions, however, probably won't ever see the light of day. Perhaps they rely on things that are physically impossible, like exceeding the speed of light. Maybe they're made from materials we don't have access to, like the vibranium and uru of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Whatever the reason, some fictional inventions are unlikely to make the transition from fiction to reality. Here are 15 of my favorites.

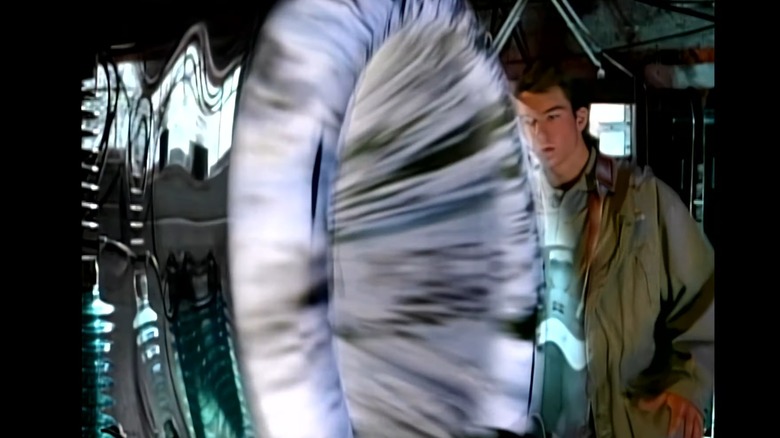

Sliding timer from Sliders

In 1995, college student Quinn Mallory (Jerry O'Connell) accidentally opens a portal to another universe while trying to build an anti-gravity machine in his mom's basement. After a few preliminary experiments with a basketball and a cat, Quinn leaps through the portal and finds himself in an alternate reality where up means down and stop means go.

Over the next five years, he and his friends Wade Welles (Sabrina Lloyd), Professor Maximillian Arturo (John Rhys-Davies), and Rembrandt "Crying Man" Brown (Cleavant Derricks) explore dozens of alternate Earths in an attempt to find their way home. Each of those worlds is different from ours in at least one way. On one, the dinosaurs never went extinct, while on another, the culture of ancient Egypt has spread around the globe.

All of that travel through multiversal subspace is facilitated by a sliding timer that opens a gateway to the next world and dictates how long the sliders have to stay there. Building a handheld gadget that rips a hole in spacetime probably isn't in the cards, and if "Sliders" is any indication, that's probably a good thing.

Neuralyzer from Men in Black

In 1997, science fiction fans were introduced to the Men in Black in a movie of the same name. In the film, based on the Marvel Comics series "The Men in Black," Earth is home to countless alien refugees from all over the cosmos. Their activities are monitored by the Men in Black, who intervene when the human population becomes aware of its alien neighbors.

The fictional Men in Black are, as the Will Smith song suggests, the first, last, and only line of defense against the worst scum of the universe. To maintain the illusion of an alien-free existence, the Men in Black use a collection of high-tech gadgets, including a handheld device called a neuralyzer, which erases the memory of alien encounters and anything else.

The device works by isolating and measuring the electrical brain impulses related to memory. A flash from the neuralyzer puts a viewer into a suggestible state, during which agents can replace those actual memories with more mundane fictional ones. Using dials, an MIB agent can dictate how much time to wipe, erasing the last few minutes or the last few decades.

Pizza hydrator from Back to the Future Part II

In "Back to the Future Part II," Doc Brown arrives just moments after the conclusion of the first film, telling Marty that they must travel to the future year of 2015 to save Marty's children from ruining their lives. In that incredible future, Doc and Marty find all sorts of high-tech inventions, like flying cars, self-lacing shoes, and hoverboards.

The most delicious invention in the movie is the food hydrator, which allows a user to put tiny dehydrated foods inside and transform them into a hot and fresh dinner, practically instantly. The fictional machine was manufactured by Black & Decker (the company hadn't yet switched to Black+Decker when the movie was made), was voice-controlled, and featured various levels of hydration for different types of foods.

We see a dehydrated four-inch pizza enter the machine and come out as a 12-inch pizza, ready to eat in just 12 seconds. While dehydrating and hydrating foods are things we do regularly in the real world, the process takes considerably longer than 12 seconds and doesn't happen inside a microwave-like machine.

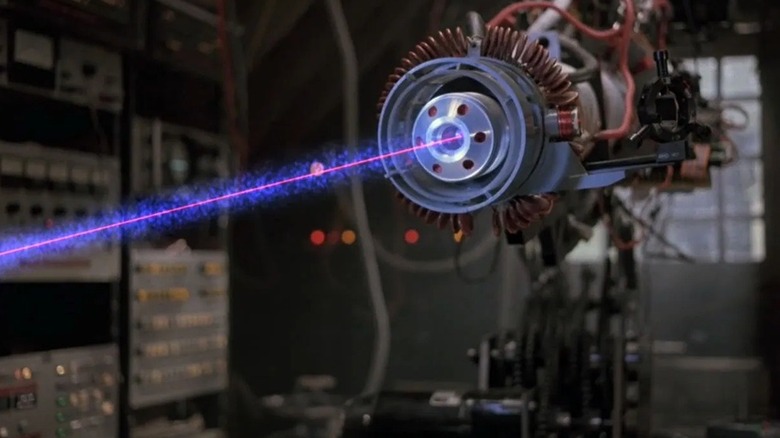

Proton pack from Ghostbusters

When a trio of parapsychology professors run into a ghost at the library, they promptly get themselves fired. They create a new business dedicated to locating, investigating, and capturing ghosts. They're basically a pest control service for poltergeists in the 1984 supernatural sci-fi film "Ghostbusters."

The Ghostbusters are a ragtag group of spirit hunters who are the only thing standing between the real world and supernatural destruction. They keep wicked specters at bay with the help of the stylish Ecto-1, ghost traps, and the iconic proton pack.

Invented by Dr. Egon Spengler, the proton pack uses a miniaturized particle accelerator to create a stream of positively charged particles (protons) that latch onto the negatively charged ghosts. That particle stream lassos ghosts until they can be sucked into a ghost trap. Just make sure not to cross the streams. While particle accelerators do exist and are used by scientists to do cutting-edge particle physics, the portable backpack cyclotron designed for trapping ghosts has yet to materialize.

Transporter from Star Trek

As the name suggests, "Star Trek," in its many iterations, is about a trek (or many treks) through the stars. Much of that journey happens courtesy of a faster-than-light warp drive, which lets the crew travel huge distances across the Alpha Quadrant of our galaxy with ease.

For shorter trips, like from the Enterprise to a planet's surface or between the ship and a space station, crew members can take a shuttle, or they can use the transporter. A shuttle works the old-fashioned way, by moving matter through ordinary space. The transporter, by contrast, is essentially a teleporting machine that transforms a person into an energy pattern and then reconstitutes that person on the other end.

While teleporting instantly between here and there would arguably be the best way to travel, you do have to contend with the existential implications of being broken down at an atomic level and rebuilt every time you need to go somewhere. Information has been teleported using quantum entanglement, but teleporting actual matter, like Seth Brundle, probably isn't in the cards.

Shrink ray from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

The family science fiction film "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids" (1989) was followed by two sequel films, "Honey, I Blew Up the Kid" (1992) and "Honey, We Shrunk Ourselves" (1997), as well as "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids: The TV Show," which ran from 1997 to 2000.

In the first film, Wayne Szalinski (Rick Moranis) is an aspiring inventor whose creations don't always work the way they're supposed to. Wayne builds a big ray in his attic that can ostensibly shrink and grow objects, but every time he tries to use it, the target object explodes. After an unfortunate accident involving a stray baseball and a broken window, the shrink ray shrinks the Szalinski kids and the kids next door.

In-universe, the gadget works by reducing or increasing the space between atoms, making an object smaller or larger. In the real world, the laws of physics stand in the way. The only way to push atoms more closely together is in extreme scenarios, like the fusion that occurs in the hearts of stars or the degeneracy pressure of a white dwarf or neutron star.

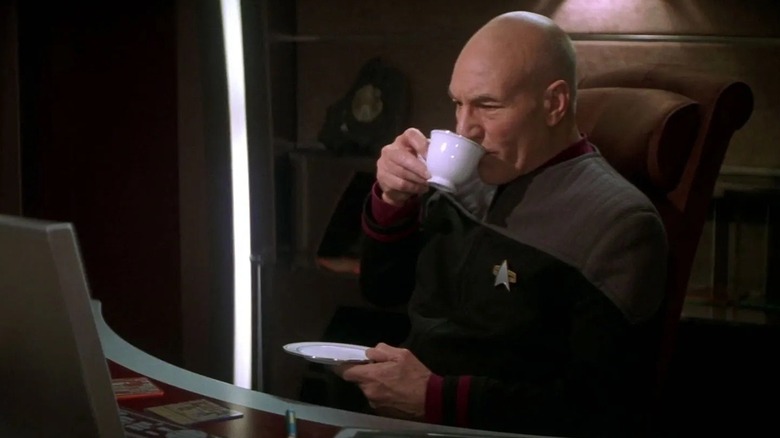

Replicator from Star Trek

There are few pieces of fiction that have generated more cool future technologies than "Star Trek." When they're not busy running the ship or playing games on the holodeck, the crew of the Enterprise can create food and supplies from thin air using the ship's replicators.

In the original series, food synthesizers were used exclusively to create food and drink. By the time of "Star Trek: The Next Generation," those synthesizers had evolved into the more generalized replicator, capable of synthesizing almost anything you could want, with a few exceptions.

Replicators transform energy into whatever you might need, from food to spare parts, but there are limitations. Importantly, it's not creating something from nothing. On "Star Trek: Voyager," we see the crew using replicator rations to conserve energy on their decades-long trip back from the Delta Quadrant. In addition, Federation safety protocols prevent the creation of dangerous materials like weapons or antimatter, and replicators can't create anything living. Replicators are all the rage in the 24th century, but here in the 21st, we have to satisfy ourselves with 3D printers.

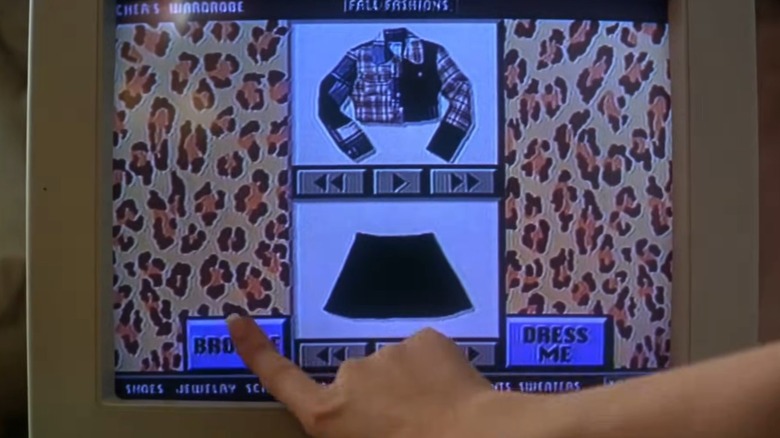

Digital wardrobe from Clueless

Loosely based on the 1815 novel "Emma" by Jane Austen, the 1995 teen comedy "Clueless" introduced us to Cher (Alicia Silverstone), Dionne (Stacey Dash), Tai (Brittany Murphy), and the rest of their high school peers. Cher lives a privileged life in Beverly Hills, where her lawyer father gives her everything she could ever want, including a Jeep Wrangler that she doesn't really know how to drive and an expansive wardrobe.

Star-studded and quotable, the movie is entertaining even three decades after its release, and the costume design wonderfully captures the unique aesthetic stylings of the 1990s. From the outfits to the slang, everything about the movie's design is unmistakably '90s, save for one futuristic prop.

When most of us get dressed, we have to get up, open the closet, and flip through clothing items manually. When Cher peruses her collection of designer outfits, she does it virtually. A digital interface presents images of individual clothing items she can mix and match like a paper doll. Using the digital wardrobe, Cher can try out different combinations to create a unique look. Then, when she lands on something, the wardrobe presents those items to her. We could definitely build Cher's digital wardrobe if we wanted to, but it probably isn't practical for most of us.

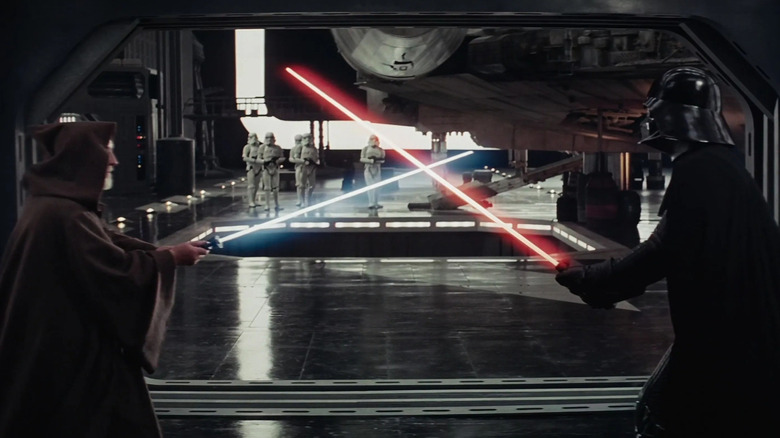

Lightsaber from Star Wars

Viewers were first introduced to the lightsaber in the original "Star Wars" film, when Ben Kenobi describes it as "an elegant weapon for a more civilized age." You can find lightsabers only in a galaxy far, far away, where they are wielded by Jedi Knights and their Sith adversaries.

Lightsabers come in various styles, with single or double blades, straight or curved hilts. And, of course, there's Kylo Ren's infamous crossguard lightsaber. It's one of the most iconic elements of the "Star Wars" saga. A lightsaber can cut through doors, deflect laser fire, and appears in every single "Star Wars" film.

Most of the time, a lightsaber exists as a small metal hilt. When active, however, that hilt produces a plasma blade a few feet long. Those blades are usually blue or green, but they come in other colors. The color derives from a kyber crystal inside the hilt, which also constrains the plasma and binds it in a blade-shaped field. Lightsabers are as unrealistic as they are cool. In the real world, we can create beams of light (lasers), and they can even be powerful enough to cut through objects and injure people. But we haven't figured out how to make that light curl back on itself, and it's unlikely we ever will.

PASIV dream machine from Inception

Christopher Nolan's 2010 dream caper "Inception" is a visual spectacle with some heady ideas. Dom (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) are dream thieves who use experimental technology to get inside a target's head and lift information from their subconscious. It's a dangerous job, but not as dangerous as what they've been asked to do.

The latest job isn't to take information out of someone's head, but to implant it. With help from a few friends, including dream architect Ariadne (Elliot Page), Dom and Arthur sneak inside the mind of Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy) to convince him to break up his father's company and to make him think it was his idea.

The whole enterprise is made possible by the PASIV device, short for Portable Automated Somnacin IntraVenous Device. As the expanded name suggests, the device delivers a drug called Somnacin to facilitate the shared dream experience. In the real world, scientists have made some progress in decoding dreams, but entering a shared dream space remains an impossibility.

Babel Fish from The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy

Arthur Dent is having a bad day when he finds himself aboard a Vogon spacecraft at the beginning of Douglas Adams' "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy." When the extraterrestrial Vogons start speaking over the ship's communication system, Arthur can't understand them until his friend, an alien, puts a fish in his ear. Normally, that wouldn't improve your situation, but this was a Babel Fish.

The Guide describes the Babel Fish as "small, yellow, leech-like, and probably the oddest thing in the universe." The fish feeds on brainwaves, not from the host but from everyone else nearby. Then it converts those brainwaves into something compatible with the host. Put simply, it translates speech in any language (even languages it has never heard before) so that you hear it as if it's being spoken in your language. In doing so, the Babel Fish feeds itself. You can imagine how useful that might be, unless you're about to hear some Vogon poetry.

Many science fiction stories rely on universal translators to allow people from different planets and cultures to communicate with one another, but the Babel Fish is one of the funniest and coolest examples. Real-time translation devices have replicated the Babel Fish to some extent, but we're far from a truly universal real-time translator.

Digitizer from Tron

ENCOM is a fictional company specializing in computer hardware and software, including the popular video game "Space Paranoids," stolen from former employee Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges). By the beginning of "Tron" (1982), Flynn is running an arcade and fiddling with cutting-edge computers on the side.

Hoping to find evidence of ENCOM stealing "Space Paranoids," Flynn first hacks into the company's system and later breaks into the building. There, he encounters the much-improved Master Control Program (MCP), which uses an experimental digitizing laser to upload Flynn to the Grid. That's where Flynn discovers an entire digital world inhabited by programs that look and behave like people.

The digitizer works by converting physical matter into digital information and transferring that information to a computer server. Later on, the digitizer reverses the process to reconstitute Flynn in the real world. The closest thing we have in the real world is probably a 3D-scanning laser, which can create a detailed digital model of a real object or person. Actually transporting someone into a digital space is a bridge too far.

Jetpack from The Rocketeer

In 1991's "The Rocketeer," stunt pilot Cliff Secord (Billy Campbell) comes into possession of an experimental rocket pack created by a fictionalized Howard Hughes. Secord is used to piloting planes, but the rocket pack gives him the ability to fly essentially on his own, without the aid of an airplane.

Jetpacks and related devices have been a mainstay of science fiction for decades. For practically all that time, fans of science fiction have been wishing and waiting for jetpacks to leap off the page and screen.

With the exception of things like Yves Rossy's jet-powered wingsuit and a few others, jetpacks or rocket packs remain confined to science fiction. Even the most promising jetpack technologies are limited in both time and range, and they're difficult to fly, requiring lots of training. The dream of people whizzing around on a whim using personal jetpacks is unlikely to become reality anytime soon.

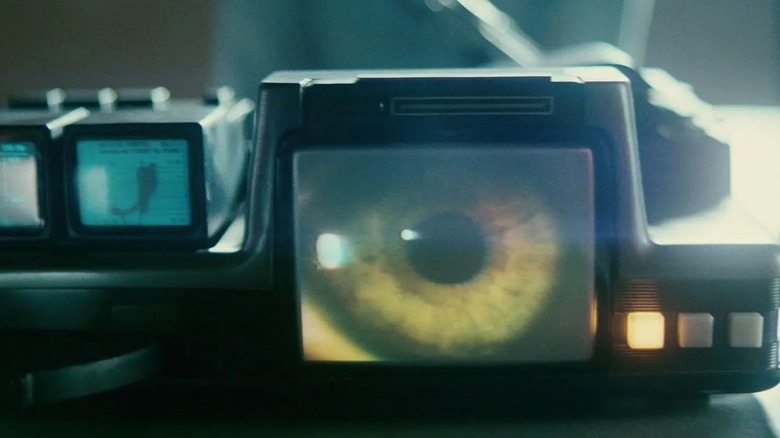

Voight-Kampff machine from Blade Runner

The "Blade Runner" films, loosely based on Philip K. Dick's "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" take place in a version of Earth inhabited by both humans and replicants, advanced androids that look and behave like people. Some of them even believe they are people.

The first film hit theaters in 1982 and imagined a fictionalized Los Angeles in the far-future year of 2019. There, blade runners like Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) track down and retire (kill) replicants. It's not an easy job, especially because modern replicants can pass as human. To distinguish the artificial people from the real ones, blade runners use a device called a Voight-Kampff machine.

The machine works somewhat like a polygraph. It measures a person's breathing, heart rate, blush response, and other physical characteristics while they are asked a series of questions. It's intended to identify the non-humans by triggering an unusual emotional response. In the real world, the closest equivalent might be the emerging struggle to know what's real and what's artificially generated by an AI model.

Stargate from Stargate

In the film "Stargate" (1994), a military project attempts and fails to decipher the hieroglyphs on an ancient piece of technology found in Giza, Egypt. The project recruits Egyptologist Dr. Daniel Jackson (James Spader) to lend his expertise.

Almost as soon as he sees the hieroglyphs, he deciphers them. Having accomplished this, he's taken to see the Stargate, a large metal ring bearing the same hieroglyphs he's just deciphered. Using the information provided by Jackson, the military activates the Stargate for the very first time.

The markings correspond to constellations, and when put into the right configurations, the Stargate opens a doorway to somewhere else in the cosmos. Jackson and his military escort step through the gate and arrive on the distant planet Abydos, where the Egyptian god Ra, who is actually a long-lived extraterrestrial, rules with an iron fist. The drive to quickly travel across interstellar space is powerful, but when we do travel to the stars, we're going to have to do it the old-fashioned way.